By James Odermann

DCA Writer

“I am 89 years old, but I feel like I am only 87.”

This witty summation of Brother Placid Gross characterizes his role as the elder monk at the Assumption Abbey Monastery in Richardton. In December, he celebrates 67 years as a member of the Benedictine community reflecting succinctly, “That is a lifetime.” In between, however, Brother Placid (baptized Aloysius Gross in 1935) has poured a lot of vocations into his lot in life: carpenter, printer, monastic leader, farmer, rancher and—most recently author.

Brother Placid’s life has been characterized by humble obedience, listening to the quiet messages of God delivered in subtle ways by his family, friends, peers and superiors. “When people talk about vocations, people like to hear it was a lightning strike. My story is not dramatic,” he said. “I did not hear a crack of thunder or lightning. It was very gradual over a period of years, a period of time.”

His early life was like most depression-era Germans from Russia, who were one of two generations removed from immigration to North Dakota. He was one of 16 children born into the family of John M. and Magdalena (Vetter) Gross of which three died as babies.

His mother set the standard for family longevity living seven months past her 100th birthday. The oldest child, Mathias, celebrated his 101st birthday on October 7, this year. The youngest was Leo, born in 1946.

Brother Placid proudly recounted his brother John will become a centenarian on November 7, his brother Benedict was 94 on September 1, his brother Valentine is 92 and his sister Anna Marie is 90. At 89, Brother Placid says, “There are three more younger than I, but they don’t count; they are young.”

Life as a youngster for Brother Placid was typical of large farm families in Logan County, near the small town of Napoleon. German was the language spoken at home. Every family member was expected to share in the workload.

He said, “All I did was work . . . In the morning, we did the chores and came in for breakfast and right after walked to school one mile. We walked all the time.”

Yet, Brother Placid was direct about the lessons he learned growing up. “It was more good than having no responsibility, having nothing to do. We had to learn to get up, get ready and be responsible for our own life.”

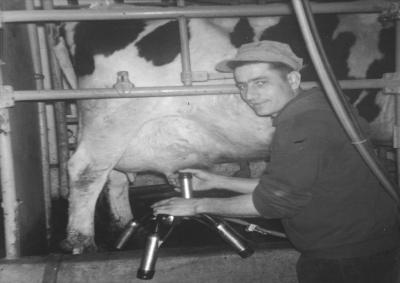

In 1948, he graduated from grade school and kept living and working on the farm, which, according to his estimate totaled about 1,000 acres with owned and rented land. “All the brothers stayed home and helped on the farm,” he said. “We milked 25 cows morning and night by hand.”

Generational differences between today and Brother Placid’s youth were something he highlighted. German Russian children were never bored. There was always work and, as he pointed out on page 213 of “Prairie Wisdom,” bored children were instructed to “go stand on your head.” (This long-standing physical feat was performed by Brother Placed at the 50th anniversary of his profession.)

His personal discipline and commitment to hear God’s word, however, were major factors in his decision to join the Benedictine community at Assumption Abbey. “We prayed before meals. We said the rosary a lot—especially during Lent—and we went to Church,” he said, noting “Dad was the organist.”

Brother Placid continued working on the family farm until he was 22. “I was old enough to do something, able to make a decision and came to the Abbey,” he said explaining “it was the closest abbey to home. I felt I wanted to do something good, to contribute something to mankind. I prayed for the right decision to do what I should do. I had never seen a monastery, never seen a monk. It is kind of different in what you do now-a-days.”

He answered the call joining the Benedictine monastery on December 1, 1957. “It certainly was the grace of God working because I came here and had a tour, a two-hour visit, and two weeks later I came here to stay. It was kind of weird how it happened,” he said. “Our pastor told us to pray for the right decision in your life and I always did that and just gradually I had the idea of doing something good for mankind, for people.”

He has never looked back. He took first vows and profession in 1959 and final profession in 1962, answering the call of obedience, one of the precepts of the Rule of St. Benedict.

While he had grown up working on a farm, he had no thoughts of working as farm manager at the Abbey. “When I came here, I did not envision this. I did not envision anything, I had no plans for my life, . . . I thought that was what God wanted me to do,” he said. “An angel did not come and tell me, like the Virgin Mary, but I did what I thought God asked, only God did not ask me out loud.”

As a monk at Assumption Abbey, Brother Placid was deeply immersed in spiritual development. His background and skillset, however, resulted in Abbot Ignatius Hunkler assigning Brother Placid to the Abbey farm where he shared duties with fellow community members.

Abbot Robert West named him the farm manager in 1967—and Brother Placid flourished in that role until the Abbey made the decision to rent the agricultural portion of their land holdings to area producers. Brother Placid led the establishment of the Abbey farm as a progressive, conservation-minded agricultural operation. He and the Abbey received regional recognition for exemplary work.

“I was not anxious to work on the farm, but I did what was asked,” he said. “I was not anxious to be in charge. There was a lot of stress, a lot of responsibility, a lot of work . . . it was good for me, it was good exercise . . . this was part of the vow of obedience . . .”

Through his commitment to excellence, Brother Placid is part of the monastic community that makes prayer a central theme of life. The Abbey community day begins with prayer and ends with prayer. “Life is a prayer,” he said. “Prayer is a big part of my life.” The community offers official prayers of the church—the psalms—and other prayers five times a day.

Brother Placid recalled his early days as a member of the Abbey farm, when Abbey Prep School and Assumption College were part of the community. The Abbey farm provided most of the food for the students and community members.

He recalled, “We butchered the beef and pigs. It was a full-time job for one brother . . . we butchered one beef and three hogs a week for consumption.”

Despite the workload and his lot in life, Brother Placid is happy with his choices and his life. “I did not know what I was going to do but I certainly did not plan on farming. It was okay as a vocation. I feel I fit in better on the farm than doing some other thing.

“I would not want to live my life all over. It is not necessary. If I could live it over, well, this is what I was supposed to do—and that is what I did.

“Life is like a wisp of fog. It is here and then it disappears. Life is short,” he finished.

Posted with permission of Sonia Mullally, Editor, Dakota Catholic Action. December 12, 2024.